I listened to a fascinating NPR podcast this weekend about the history of housework and how new designs and smarter technology have – over time – shifted household duties, rather than replaced the labor surrounding them. Essentially, the saving of labor and the making of leisure are two entirely different things – we are saving time, yes, but where is that time going?

I’m endlessly interested in the role that objects play in our lives, especially when centered around ease and simplicity and everyday life. Managing a household has always been a full-time job, but now that we’re not hand-soaking our laundry or darning our clothes or growing our own dinner – what are we doing?

The podcast presents the idea that, historically, household duties were performed in community, rather than in isolation. Washing machines brought laundry indoors rather than on a shared clothesline. Refrigerators reduced trips to the grocery store. Sewing machines made knitting and darning and mending in a circle with children running underfoot nearly nonexistent. For many household duties, the rise of technology brought a rise of isolation, trading outlets and plugs for outdoors and people.

It’s the whole “whistle while you work, a spoonful of sugar, it takes a village” mentality. Working can be fun when performed in groups, if for no other reason than the simple idea that we’re working with our hands in a state of conversational flow. Swiss Japaneses designer Nadine Fumiko Schabu agrees, devoting much of her work to exploring an emotional bond between her products and their users.

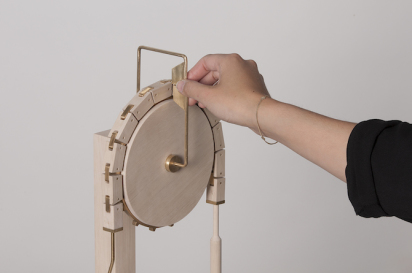

“In order to verify the desired weight [of this kitchen scale], the user must actively interact with the scale by touching the pointers,” Nadine writes. “Our fingers are capable of sensing the slightest change of discontinuity – when the weights are balanced, the fingers will sense perfection. This interactivity is essential in order to fully experience the product; allowing for a relationship to burgeon.”

And it’s a valid thought: interacting more often and to an advanced degree with the things around us might cause our appreciation for each object to grow. The added benefit? Working with our hands makes us happier.

“We are programmed to reward ourselves when we accomplish things with our hands,” Harvard neurologist Marie Pasinski, MD explains in this surprising article. Psychologist Susan Pollak, EdD goes on to agree: “I think for so many people, it just feels as though everything’s going so fast — life, kids, hundreds of emails a day — and there’s so little we do now that you can really see and hold on to. Working with one’s hands is a way to slow down, to savor, to take pleasure in life again.”

It’s a comforting idea, but a challenging task, choosing the scenic route over the fast track. Here’s to slower mornings, “harder” work and an appreciation for what surrounds us.

Image Credits: Nadine Fumiko Schaub

p.s. Slow shopping.

I’m with it. I set aside a typical career path after college to pursue more fulfilling hands-on work with the Forest Service.

It ended up being a natural insomnia inhibitor. Hard work = restful sleep and a happier life.

Thanks for sharing something so valuable.

Sounds WONDERFUL, Terran! Thanks for sharing!